by Claudia Flaig

Alena’s need to look after younger children in the group and also to take responsibility for them is particularly strong. Therefore, the suggestion of the course leader (IHVO Certificate Course) immediately convinced me to let Alena (she is now 4;6 years old) lead a small gymnastics group. (See Alena, 4;1 Years.)

Such a task corresponds to her willingness to help and also enables her to learn a few things: to take a back seat, to consider the needs, expectations and ideas of other children, to acknowledge them and to respond to them. These are all important social skills that also create recognition and friends. At the same time, the other children benefit from Alena’s wealth of ideas.

… in brief…

The author sees a social talent in four-year-old Alena, but also sometimes an impatient, unfriendly behaviour towards other children in the group.

To encourage her, she lets her lead a very small group – with two other children.

Alena receives guidance from the author, her kindergarten teacher, and it becomes clear that Alena learns quickly.

Preliminary talk with Alena

I tell Alena that she can do gymnastics with a small group of three to four children if she likes. I would have expected her to choose either three clever three-year-olds or three two-year-olds from the group for this. But without much hesitation she chooses Sina (3;2) and Amar (4;3) and justifies it like this: „I take Amar because he is a big child and still has to learn a lot better, and Sina because she is a girl. Because I think she’s nice.“

Amar’s overall development is very delayed. The children in the group also notice that he has special behaviour patterns. So he urgently needs support, which Alena surprisingly sees completely correctly.

Sina is an exceptionally bright, clever, overall very well-developed girl and helpful.

I must express my respect to Alena for this combination.

(Note from the course leader:

Did you do it too?)

For Amar, this mini group is manageable, he will like that. He is already overwhelmed in small groups with five children. Alena doesn’t want to take more children, at most a second group.

Alena immediately has ideas about what she can do with them:

-

- sliding on benches,

- use wooden sticks,

- ball games („Sina rolls it to me, and I roll it to Amar“),

- running games („You can run there“),

- rolling boards („Everyone will have the board for a long time“),

- gymnastics with hoops.

I suggest to Alena that she think about a theme at home. Tomorrow she could go to the gym with me and the two of them. „I can draw it,“ she says.

First gym lesson (35 minutes)

The next morning at breakfast, Alena explains: „I’ve thought of something: I’ll do gymnastics with the cardboard tubes. We lay them next to each other and put a mat on top. Then Amar can stand on it and Sina can jump on it.“

Alena already differentiates the different abilities of the two children in her imagination.

After breakfast we go to the gym. Sina has no gymnastics kit. „It doesn’t matter, then you do gymnastics in your underwear,“ Alena says. After they have changed, Amar wants to run. I draw Alena’s attention to this. She asks him to run. Then Sina has to go to the toilet and I go with her.

When we come back, Alena and Amar are already playing with the mats. Sina runs over and plays along. Amar runs across the mats shouting: „I am Spiderman!“ Alena shouts, „First you take your cabbage head!“ I am totally horrified and apparently look it, because Alena says to him very kindly, „Shall I get you rolling boards, Amar?“ When he doesn’t answer, she tries twice more to get an answer from him. I whisper to her that she hasn’t spoken nicely to him either and that he might be sad now. Alena goes to Amar, takes him by the hand and goes with him to the materials room. Sina goes with her and the children come back with wooden sticks.

I remind them of the plan to build with cardboard tubes and mats. „That also works with wooden sticks,“ says Alena. Sina wants more sticks. Alena runs off. I ask her to take Sina with her. Together they sort the sticks and the mats, and Alena says, „I’m going to say a name now: Sina!“ I explain to Alena that she should politely ask the children to do gymnastics, that she should ask and thank them. Immediately her tone changes.

While Sina follows her instructions with an open mind, Alena is obviously annoyed by Amar’s clumsiness. She rolls her eyes, takes a deep breath and gets louder.

I ask Sina and Amar to hop on the small mat, take Alena aside and explain to her that Amar needs very specific instructions, that she best shows him what to do.

She implements this immediately and says:

„Come, Amar“, looks at me and adds „please“.

They play on the wobble mat; Alena makes faces and shouts, „Now I’m a dragon!“ Sina says she is a little fox who is hiding from the dragon because he is afraid of the dragon. Amar watches, Alena asks him, „What would you like to do, Amar?“ Amar wants to fight. She gives him a wooden stick and he hits the mats.

(Instructor’s note: Super, how quickly she learns!)

Alena goes into the next room and says she wants to change and comes back with a red cloth band. Amar, looking frightened, stops punching and only continues to fight when the dragon has run past him. Then Sina wants to be the dragon.

While Sina holds on to a wooden stick with Alena, Alena tells the story of Little Red Riding Hood. „And now we’re going to get balls and skittles,“ she says. I suggest this for next time and think that we should now come to a conclusion. Alena says, „Little Red Riding Hood has died.“ Then the children do another familiar closing game and get dressed.

Although the children had a lot of fun, I found this activity very restless. Next time, an outline of the content should be planned in advance. Alena’s address to the children should become friendlier, the commanding tone should disappear from her address over time. Amar needs a lot of praise and personal attention. Alena can ask Sina to demonstrate some things to Amar. She could also ask Sina and Amar for suggestions.

After the gym lesson, I praise Alena and talk to her about my suggestions. I remind her that she suggested that I draw a picture of what could be done on a certain theme. I praise this idea and suggest that we will do this before the next gymnastics lesson.

(Note from the teacher:

It’s good that you immediately have ideas for Alena’s further qualification. It’s like a trainer’s course!)

Planning the second gymnastics lesson

A week later I ask Alena if we can sit down together to plan the next gymnastics lesson. She enthusiastically agrees and we sit down in the office to be undisturbed.

Alena is calm and focused, she wants to do gymnastics with ropes. I emphasise that she should now only think about activities with ropes. Alena: „Too heavy, I’d rather use balls.“ That’s typical for Alena: if she doesn’t have an idea right away, she’d rather leave it alone. I grin at her, shake my head, she grins back and I say, „What do you think of ropes?“

Note from the course instructor:

Great reaction from both of you!

And now she has five suggestions at once: Horse – dog – rope from the ceiling (but we haven’t) – put rope on the ground and jump over it, walk, run – wild chickens.

Alena draws her suggestions on cards to take to the gym.

Memory card: Playing horse

I explain to her that she should pay attention to what suggestions the two children make for gymnastics with ropes. She then has to respond to them so that the children also enjoy gymnastics and like going to the gym with her. Alena answers: „Then I say: go ahead. But if they do it wrong, I show Amar properly.“ I agree and ask her which of the two children can do gymnastics better. Alena: „Amar doesn’t look right, that’s why he can’t do it.“

We talk again about how important praise is for Amar. She should also have a card to remind her to praise. She says she can write her name, then she knows to praise. I am gobsmacked and let it stand.

Second gymnastics lesson

In the gym, the children get changed and I show Alena their painted cards: dog, horse, ladder, praise – she then usually says, „You did a nice job.“

I ask Alena to fetch the ropes from the next room. „Sina is a girl, she get the red one. Amar is a boy, he get the blue.“

„We’re going to play horse!“ All three of them run through the hall at a gallop, whinnying and waving their ropes. Then Amar pulls his rope behind him as a snake. Alena, alerted to this by my hand signal, immediately says, „We’ll all make a snake like Amar!“

Then Alena tries to step on Amar’s rope, he is anything but enthusiastic about it. I tell Alena to explain this kind of game of tag. She does that very well and the three of them play it for a while.

I show Alena her cards so that she can choose another game. Sina looks over her shoulder and says, „Tie the rope around your belly.“ Alena: „Yes, you are a dog, Sina. Get on all fours!“ She ties the rope around her and leads her around the room, Sina crawls around barking. Amar also crawls off straight away and I tie the rope around him. „You’ve already done that really well!“ says Alena – without me showing her the praise card. Amar beams: „Or cat!“ he answers and meows. „Or do you want to be a frog?“ asks Alena. „No!“ roars Amar. He is a wild cat and has a lot of fun. He says: „Sina’s turn!“ Sina jumps like a frog, I show the praise card and Alena praises: „You did that nicely, Sina.“

Now Alena suggests building a ladder. While Sina actively helps, Amar looks on with interest. I encourage Alena to lay down a rope together with Amar. They walk, hop and crawl over the ladder in different variations. Without prompting, Alena praises again and again.

After our balloon farewell game, the children get dressed and Alena says, „Amar was really good today, wasn’t he?“ And I confirm: „But you helped him really well, Alena. You did a nice job!“ We smile.

I ask Sina and Amar if Alena is a good gym teacher. Sina: „Yessss!“ – Amar: „It was fun!“

When asked if they want to do gymnastics with Alena again next week, Sina answers, „Yes, but only Amar and I!“ Amar also wants to do gymnastics again. Alena looks very pleased.

I praise Alena again for taking Amar into consideration, praising him a lot and that’s why he did particularly well today.

It was really a calm, structured situation.

Planning the third gym lesson

I go with Alena to the materials room in the gym. She decides on a gymnastics lesson with scarves. Her suggestions come without any hesitation:

-

- Put the cloth down, stand on it and slide around the room,

- Swinging the cloth,

- Putting the ball on the cloth, carrying it and jumping,

- Putting the cloth over your head,

- Tie a buccaneer headscarf (dress up),

- Tuck the cloth into the trousers, run away, one child is the catcher,

- Run while keeping the cloth hovering on the chest.

Reminder card: Balancing the scarf on the head

Reminder card: Game: Catcher must grab scarf.

I remind her how important praise is for Amar. While drawing the cards, she draws a smiley face in the side view and wants to know how to write „praise“.

Reminder card: Praise (in German: Lob)

Then she also wants to draw a sad smiley to show the children when they are „not good“. We talk again about the different abilities of people, about talents and deficits. I emphasise that everyone has strengths too! I remind her that Amar knows all the makes of cars, that he was the only child who could still complete a new spell. However, he has problems repeating very simple things spontaneously and that he depends on her help in these cases.

When I ask Alena if she thinks Amar realises that he can’t do many things as well as other children, she answers yes. So we don’t need to tell him or show him.

Only praise gives him courage.

Alena puts the cards away, she is done.

Third gymnastics lesson

Alena is the last to arrive at the group in the morning and makes a decidedly bad-tempered impression. Nevertheless, she asks first if we are going to do gymnastics now. She has to wait a little longer and goes to the painting table.

In front of the gym, she wants to have the key and unlock the door herself. She lets me help her open the door. She immediately helps Amar to change, which he gladly accepts. He can do it on his own, but it takes forever. I don’t ask whether Alena helps him to save time or out of helpfulness. I don’t want to overdo it with criticism.

When the three of them have moved, Alena looks at me grimly. When I ask her what she has thought of for today, she says she doesn’t remember. I point to the cards lying on the windowsill. She takes the cards, looks at them, goes into the next room and gets the box with the cloths.

„Do you like to ride with cloths?“ she says, turning to Sina. Sina starts immediately, I seek eye contact with Alena and draw her attention to Amar with a movement of my head. She looks through me. I raise my eyebrows questioningly. She holds eye contact – but again nothing. „Maybe Amar and Sina have ideas too, Alena!“ I say. „Amar always has baby ideas,“ she replies. Then she turns to Amar: „What do you want to dress up as – please dress up, Amar!“ – „I want to be a buccaneer!“ he says and tries to tie the scarf over his head, while Sina simultaneously slips with her scarf and cries. Alena runs to her concerned and comforts her, I help Amar.

Now Sina wants a skirt. While Sina and Alena are dressing each other up, Amar runs through the hall and shouts, „I’m a buccaneer!“

He sits down on the mat in front of the mirror and says this is his pirate ship. „Amar is my prince,“ says Sina. Alena demands that she wants to be a princess too. Sina would like a veil, but Alena says, „No!“ I explain that veils go well with princesses and Sina gets another scarf. Alena accepts without showing any emotion.

Amar runs through the hall again, shouting that he is a tiger, then a dragon and finally a knight. Several times Alena tries to persuade him to dress up – until Amar sulkily retreats. Alena does not let up. I ask Amar to say loudly to Alena that he does not want to dress up. Amar does so loudly and clearly.

As he walks back to his ship, Alena runs after him. Amar fights back verbally again, collects cloths and brings them to the ship. One thing is clear: for Amar, this hour is really a promotion hour. I only hope for Alena too!?

I draw Alena’s attention to her cards and try to go back to her planning and bring some structure into this lesson. I ask the children to put all the cloths in the box and ask them what else they can do with cloths. Amar throws up a cloth and catches it. Alena praises him – after I show her the praise card. (I would like to emphasise here that she does not sound annoyed or irritated when she is asked to praise).

Then the children quickly do all the exercises:

-

- Sina clamps the cloth between her legs and hops (praise card).

- Alena suggests „catching“ – everyone is the catcher for once.

- They run through the hall with the clothes on their heads.

- After looking at her card, Alena fetches balls and they transport them; invent a ball man.

Our carousel game concludes after my prompting. The whole gymnastics lesson lasted 30 minutes.

I found this lesson very exhausting. Alena was in a really bad mood, also for the rest of the day.

I have doubts:

Was she in a bad mood because of our conversation the day before when she wanted to draw the sad smiley?

Note from the course leader:

Did you ask her about it?

Is Alena perhaps overwhelmed with the way the lesson is organised?

However, through our conversations during planning and implementation, we work out forms of social behaviour such as consideration and learning how positive reinforcement works. Alena thinks about these topics and shows me understanding. I have the impression that I am strengthening Alena’s social awareness.

Note from the course leader:

That’s good. Maybe it would be a good idea to have a quiet talk with Alena in which you list all the things she has learned in these gymnastics lessons. I have noticed that you are very gentle with the three of them and try to put yourself in their shoes. These are the best prerequisites for promoting gifted children. If one of Alena’s lessons doesn’t go so well (which happens to us too), that’s not dramatic. The important thing is, if you want to end the gymnastics lessons, that the end is accompanied by a great and harmonious moment (a sense of achievement).

Amar definitely benefits from these lessons. Sina asks daily when she can go gymnastics with Alena again – weekly gymnastics seems to be too little for her. We will spend the whole of next week in an urban forest area. There we will have our, despite all doubts, desired gymnastics lesson under Alena’s guidance in the forest.

Note from the course leader:

According to our feeling, something should now come – in addition , if possible, if necessary, instead of – that not only further develops Alena’s helping social behaviour, but also her expansive one: cooperation with similarly able and quick-to-learn children. She has learnt a lot, but now perhaps feels too set in her ways as the loving, understanding, helping girl.

Another positive thing is that she has realised that you are a good learning guide. And now she has this trust in you that you understand that perhaps it should not be her life to always help slow boys, but rather to steer a rocket – as she expressed in answering the questionnaire?)

See also: Alena, 4;1 years

You can also follow Alena’s development chronologically, as far as it is documented in the articles:

Alena (5;0) Studies Letters – When Should She Enroll at School?

The Dead Mother from Pompeii and Crayons for South Africa

Alena (5;2) Gets to Know the Shadow Theatre

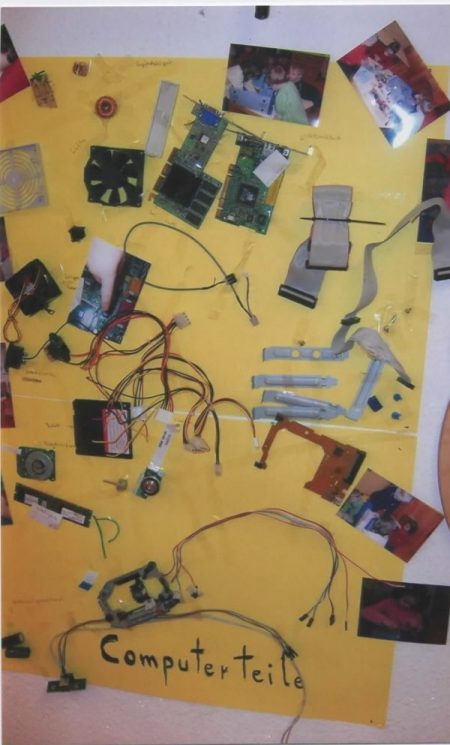

Disassembling Electric Devices

Alena (5;10) and a Small Group Are Becoming Experts in the Learning Workshop

Date of publication in German: April 2018

Copyright © Hanna Vock, see imprint