Archiv für den Monat September 2021

Bastian (6;1) Comes Out of His Shell

by an IHVO graduate (kindergarten teacher)

Bastian (6;1), who is very articulate, knows a lot and wants to know a lot, clearly rejected strangers. He also tried to avoid larger groups of people (more than five people); this could look like Bastian not entering a room with strangers or many people, insulting the people or hiding.

Bastian has a very close relationship with Nicola, his best friend, but he did not make any closer contact with most of the children in the group for years.

In the course of the „What flies, rides and swims?“ group, Bastian’s social behaviour changed.

The group of eight children, which seemed suspicious to him at the beginning, became more and more a community in which he felt comfortable, in which he could make new experiences … and show off … could show off.

He enjoyed explaining things to the other children and the children of the AG listened to his mostly very vivid descriptions with pleasure.

See also: Bastian Is Explaining His Dream Car.

Towards the end of the AG time, he even began to help and motivate younger children.

For example, he suggested to a 3-year-old girl that she reshape her lump of modelling clay, which kept sinking in the water.

When it came to creating a car out of a large cardboard box, there was a huge rush, everyone wanted to paint the box – but Bastian let younger children go first.

I can’t say for sure to what extent Bastian’s changed behaviour is a result of the AG work; in any case, Bastian now reacts more relaxed to strangers and situations. In addition, he now allows other children to be close to him and to make contact with him, and his circle of friends has increased.

Such positive changes in behaviour could also be seen in other participants of the workshop, especially in the „kindergarten newcomers“ who were still very shy at the beginning.

Date of publication in German: February 2014

Copyright © Hanna Vock, see imprint

Bastian Is Explaining His Dream Car

by an IHVO graduate (kindergarten teacher).

Bastian (6;1) explains his dream car as part of our project „What flies, drives and swims?“.

I divided the children interested in the project into two groups; Bastian is in a group of 8 children.

In the project, we have already taken a closer look at the „inner workings“ of a car, especially how a petrol four-stroke engine works, and we have also looked at the technical side of cars through books, experiments and software.

Now we meet again and I say:

„Well, if I could build a car myself, if I were the car builder, my car would look different. I would build my dream car.

Do you feel like drawing your own dream car?“

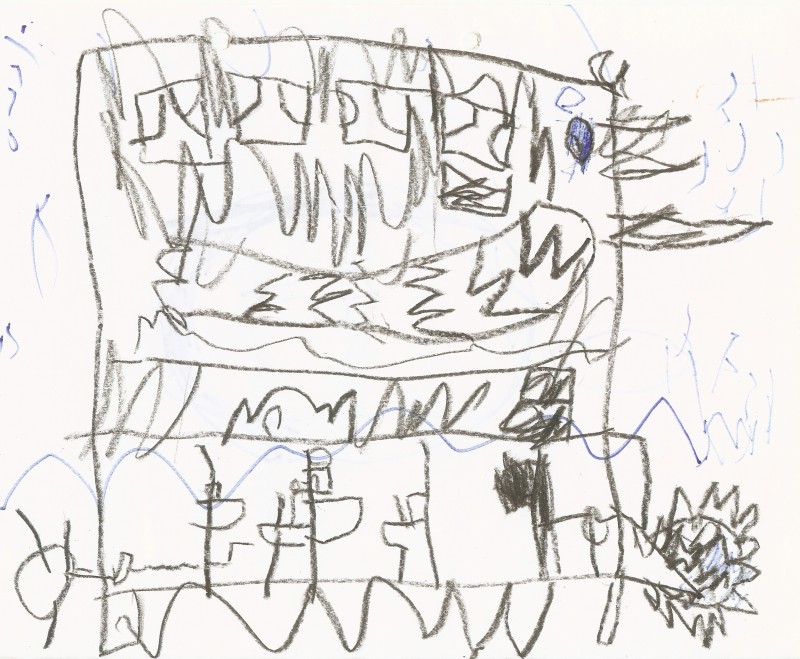

The children feel like it, they all start immediately. I briefly point out the materials provided (pens, feathers, textiles, crown caps…) and can then observe in the background.

During the painting, the children don’t talk much – I had announced that they could present their works later. Without exception, all the children, but especially Bastian, go to work concentrated and with a lot of joy.

Unlike the other participating children, Bastian rolls up his finished picture and ties a bow around the roll. I ask why; he replies, „That’s my secret plan of the car, no one is allowed to see that.“

Knowing Bastian’s determination, I fear his dream car will indeed remain secret and no one will get to see it. I realise that I would have to accept that.

We sit down in a circle.

Emma describes her car like this: „In my car there is a lift. Then people can go up and down in it.“ When I ask what she would have drawn in black, she says, „That’s the dining table and those are chairs.“ Because her car is so heavy, she explains, it needs a lot of wheels; she has drawn them in green.

Nicola, Bastian’s best friend, has drawn lots of aliens inside his car. „They can all look out of the windows – and the ones in the front, they steer the car.“ One of the children wants to know if the aliens built the car themselves or bought it. Nicola answers, „They built the car themselves, you can’t buy that on Earth.“

I ask him what else the aliens built in or on the car. „At the very front,“ he says, „there’s a thick bar. If the aliens crash into ’something‘, the car still won’t break.“

Bastian shows great interest during this and the following descriptions and finally comes forward to introduce his picture after all.

His car is a very fast car, he says. „It has a hundred cylinders, here in the front (piston-like objects in the lower half of the picture) you can see some.“

Bastian shows the other children his drawn-in cylinders. „The car is also very strong,“ he points out proudly, „it can even drive through stone! I ask him how it manages that. „It’s quite simple, it has pointed screws with which it easily drills through stone,“ he answers and shows the pointed screws. (They can be seen at the top right of the picture.) „But they have to be activated,“ he adds.

At this time I point out one of our rules of conversation to the children: „You know that you can always ask questions if you want to know something more precisely.“ One of the boys wants to know what „activate“ means. Bastian explains the term as follows: „When the car hits stone, the drills come out and drill the stones.“

I’m still interested in whether the car needs a lot of petrol. „No, it’s wind-powered. It only needs petrol when there is no wind,“ Bastian answers. I ask the other children if they know what „wind-powered“ means; most of the children shake their heads and Bastian explains: „When there’s wind, the car can drive like a sailing ship. It has lots and lots of sails.“ He shows the sails and explains that the car also has a propeller. It can also drive under water.

„Is it driving under water right now?“ asks a child. Bastian answers, „Yes, you can see it well!“ and points to the blue drawing.

I want to know what the one in the lower right corner of the picture is. Bastian: „That’s a cogwheel that digs itself into the sand when there’s a strong water current.“ „Why does it do that?“ I ask. He explains: „When the water current is so strong, the ship drifts. When the gear digs into the sand, that doesn’t happen!“

„You’ve thought of a lot, Bastian!“ I say and ask who is driving the dream car. „Like the Nicola, aliens live in it; the bedroom windows are up there. So even when you’re lying in bed, you can ‚look out‘.“

After this remark Bastian rolls up his picture again, the presentation of his work is finished. However, he is very interested in the dream cars of the children who present their work after him.

See also: Bastian (6;1) Comes Out of His Shell

Date of publication in German: February 2014

Copyright © Hanna Vock, see imprint

Playful Mathematics at Kindergarten

by Klaudia Kruszynski

Among the most popular children’s games are those that have to do with sorting, ordering, counting.

This preference can be explained by the development of the intellect. It can be observed in all children in kindergarten, although it is differently developed and advanced in different children.

Children use different objects for this purpose.

As an example, I can mention: sorting magnetic letters by colour or arranging them into two groups: Letters and numbers. Something similar happens with the plug-in games or bead chains.

If the children don’t feel like drawing, they sort the pencils by colour, length or whether they need to be sharpened or not.

In the circle of chairs, the children can tell if everyone is there without counting, without knowing how many are there. They recognise it by the fact that all the chairs are occupied. (One child is assigned to each chair.) Another relation is: There are many toothbrush cups in the washroom – each child has its own. But there is only one tube of toothpaste – it belongs to all the children.

Many party games make use of this preference. They are designed in such a way that the colour rolled is assigned a tile/pin/doll/field. These games are played by the youngest children until they recognise them as too simple and no longer want to play, or they come up with their own variations. For example, the game pieces are no longer placed, but stacked to form a pyramid. This is more difficult than going forward by colour. Some kindergartens don’t like to see this misuse because they are convinced that board games are good for learning rules. If you don’t follow the rules, you won’t be able to find your way in society later on.

I am convinced that people need a regulated world, of course, but a certain independence and flexibility are very desirable. They are, after all, the necessary prerequisite for further development and progress. A certain independence from rules, order structures, procedures, etc. indicates creativity.

Sorting

As I mentioned at the beginning, many children have a preference, even an urge, to sort the objects around them. To do this, it is necessary to perceive one property (later several properties) of the object, and to recognise it in the other objects.

Examples with magnetic letters:

-

- Put all letters of the same colour together,

- Separate letters and numbers from each other,

- Put all letters together, regardless of their colour,

- Pick out all the letters that are in my name,

- Choose the letter you want from the set,

- Arrange the letters according to the alphabet (alphabet according to a template, e.g. from a book, or from memory, e.g. according to a song: „A, B, C, D, E, F, G…“),

- Counting the letters together,

- Compare the amount of the same letters: there are 5 times „A“, but only 2 times „X“,

- Recognise the small „x“ as a „paint sign“, look for the other operation signs,

- Arrange the numbers in ascending order,

- Lay simple operations, for example 2 + 2 = 4,

- Laying patterns.

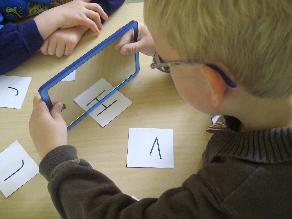

Mirror images, symmetry

Some objects have a special property: they consist of two identical parts, e.g. the wings of a butterfly, but they are mirror-inverted next to each other. Some objects can be divided into two halves with an imaginary line, which are also mirror-inverted, e.g. a top hat.

Some letters also have this property:

– A, B, C, D, E, H, I, K, M, O, T, U, V, W, X, Y.

With the help of a mirror, children can explore it wonderfully.

I have developed a game for this:

On the small cards, the letters mentioned above are shown individually. In addition, there are the same amount of cards with only halves of letters on them. The so-called „mirror line“ is also painted on these cards. The mirror is placed on it and with its help you can see the whole letter. There are different ways to play with the cards:

-

- Recognise and name the letters,

- Recognise and name the halves of the letters,

- With the help of the mirror, match the „half“ to the correct letter,

- Match the „half“ to the correct letter without the mirror.

Geometric figures can also be divided into equal halves.

Some with only one mirror line – an isosceles triangle,

some with two mirror lines – a rectangle,

some with three lines – an equiangular triangle,

some with an infinite number – a circle.

Finding this out could become an interesting game of discovery.

The circle is a special shape, it is very popular with children because you need it to draw a face or the sun. The circle is, after the cross, the next shape that occurs in the children’s representational development. At the beginning it resembles a spiral, then the children manage to close it. It takes on different shapes: Oval, egg, ellipse, until it finally gets the perfect shape. In all their attempts to paint the circle perfectly, children realise that it is not an easy task. Some children ask adults for help: „Can you paint the circle for me?“ – because they have found that their results are very far from their inner idea of what a real circle should look like. Other children look for objects to help them paint around. (The ability to recognise the circle is a necessary prerequisite for this).

So it often happens with us that the children fetch a plate from the cupboard when they want to paint a mandala. The wheels for self-made cars also have to be real circles – for this, children take the circle from the logical blocks, for example.

I thought of a game for the circle:

Bend the circle, count the parts

There are children of different ages sitting at the table, some can already write numbers, some not yet.

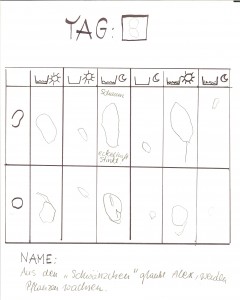

At the beginning, each player draws a circle with the help of the plate, then cuts it out. On another sheet of paper is a simple table. It has two columns: one for the number of kinks and one for the number of parts counted.

Then the circle is folded once and opened again – the children count the kinks (1) and write the number in the corresponding column of the table. Then they count the parts that have been created (2) and also write the number in the correct column.

The younger children draw lines instead of numbers.

The game is continued in this way: 2 kinks – 4 parts, 3 kinks – 6 parts, etc.

After the fifth kink, I asked children if they already knew the result without counting the parts.

Jan, (4 years 7 months) immediately knew the right number, he only counted the parts to check, then he filled in the table without bending the circle any further. He told me: the kinks always go on by „one“, but the parts make a jump over the next number.

Simon also illustrated this phenomenon graphically.

Lukas (5 years 1 month) also had no problems with this task, although he could not explain it so accurately.

Linea (4 years 8 months) wanted to play it safe and didn’t dare make any predictions.

The youngest child (4 years 1 month), of course, had enough trouble with counting the parts created and drawing the lines in the appropriate number. Nevertheless, the child was able to solve the task correctly and to his own complete satisfaction.

This task also involves doubling the number, but the children involved in the game still lack this experience.

To gain such experience, our mirror is wonderfully suitable.

With the mirror you can double everything: the shapes and the quantities. There are many ways to explore this.

Other mirror games

1. the halves of different objects are painted on small cards. Children look at these with the help of the mirror, experiencing the „miracle“ of completion.

2. the same cards are looked at without the mirror. Children guess which object they represent half of.

3. Faces that consist of two different halves are sometimes a man’s face, sometimes a woman’s face.

4. children draw the reflection in the mirror (with and without the help of the mirror).

5. children design their own cards. (To do this, they have to combine knowledge about reflections with their own creativity).

6. Children look at different objects with the mirror and notice that they get different pictures when they change the position of the mirror just a little.

7. After they have understood the phenomenon, they create „mirror patterns“, e.g. in the „hammer game“.

Set theory and statistics in kindergarten.

In the course of life, children develop the urge to sort the things that surround them. Clothes in their favourite colour are picked out from the cupboard, the red cup is placed on a red saucer, each row in the peg game is placed in only one colour, the logical blocks are put away according to shape, the coins are stacked according to colour, later according to value, and so on.

Specific game offers also promote this development, e.g. in the chair circle: Shortly before 12 o’clock, the children collect their kindergarten bags. To avoid chaos, we indicate which children should leave now: all those who have a red jumper on, or all those who have letters on their T-shirt, or who have a pigtail, and so on. Here, a child always feels that he or she belongs to a certain group (crowd), depending on what she or he is wearing that day.

The boring tidying up can also be made more exciting by providing extra bins for toys of different colours, shapes or sizes.

To do this, I thought of a few new games that I did with a small group.

Duplo Man House

20 Duplo men want to „live“ in a house. They are all different and they don’t want to be in one room. The „girls“ don’t want to live with the „boys“. The ones with red jumpers don’t want to share their room with the ones with blue jumpers, etc.

This game developed like a story (other variations would have been possible, of course).

Children looked at the little dolls and thought about which room they should put them in. They counted the quantities and wrote down the numbers. Some dolls could be assigned to several rooms.

Through precise instructions that were on the „playing cards“, all the children present were able to complete the allocation, the older ones did the writing down of the numbers.

Statistical investigation of the Duplo society

This time we wanted to take a closer look at the Duplo men, each one individually. I chose the most important criteria and prepared a statistical table. This task demanded much more attention, concentration and perseverance from the children.

To my amazement, this game became the favourite activity of several children, even younger ones.

I observed how lovingly and at the same time perceptively the little dolls were looked at by the children, how the crosses were made in the corresponding columns. (Some children didn’t need „help strips“ for this, they could locate the coordinates correctly).

One day Jan (4 years, 7 months) approached me and said he would like to prepare such a table for the children.

I thought that was a good idea, and together we thought that this time we would investigate Duplo animals.

Jan chose 10 animals from the Duplo animal box. We looked at them and thought about which criteria we could take. Jan drew the chart, but he asked me to write it on the computer because it would be much nicer (unfortunately, we don’t have a computer in the kindergarten for such games – it would be very exciting to let Jan prepare the chart).

This task was also solved with enthusiasm by several children, although Jan personally did not attach much importance to solving it correctly, he made a lot of mistakes.

Finally, Lukas did a final calculation to check who had solved the task most accurately. For this, he had to enter all the individual results and then compare them with the correct number. He worked very persistently and concentrated.

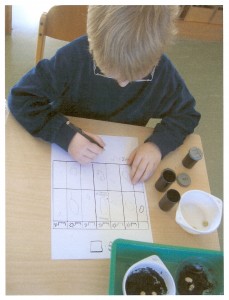

Potency

In spring, we looked at the growth of plants. We observed for several weeks how the bean seeds germinated, grew into green plants and produced flowers. Finally, we could see the pods with new seeds forming and ripening. In the first week of September it was harvest time.

There were 6 plants in the flower pot, each with 3 pods.

I worked with a small group consisting of the children who had taken care of the bean plants during the growing season.

Each child was given a large sheet of paper, a pencil and of course a harvested plant.

At the beginning the children looked at the plants, we remembered what we had observed in spring:

What was the growth like, what did the plants need to grow properly, etc.

We also noticed that each plant grew from a single bean.

The children were already very excited to see the pods, which they finally opened. They were very amazed when they discovered the white seeds inside.

Each child was asked to count their „bean children“ and write down the number. The quantities were 14 or 15 seeds. I asked the question, „How many children did the bean mama get?“ Each child gave me the answer.

Then we added up all the „children“: 88.

I asked if they knew how many children these beans would have when we put them in the ground next spring?

The children couldn’t imagine, they gave me different answers.

I drew a bean on the sheet – it was the „bean mother“, below it all 15 „child beans“.

For each „child“ I drew their children (if we were to put this bean in the ground next year).

The children supported me in painting and noticed that there would be a lot of new beans.

And if we put these „grandchildren’s beans“ into the soil, we will get very, very many beans.

In this offering, it was not important to learn exactly the true nature of mathematical power. It was important that the children developed a feeling for it.

To do this, I came up with a story:

A garden gnome called Bodo was very fond of bean stew. That’s why he put a bean seed in the ground in spring. He made sure that the seed got everything for its development: good soil, water, light and warmth. He watched his plant develop magnificently. The neighbours also supported him.

When the summer ended, the harvest came. Bodo proudly opened the 3 yellow pods and put 15 white, smooth seeds in the basket. On Sunday he wanted to cook bean stew and invite the nice neighbours over.

„You don’t just need beans for a tasty bean stew,“ Bodo thought, „you also need potatoes, leeks and carrots. And then pepper and salt. He could get that at the shop of the clever vixen Adele. In return, Adele wanted 5 bean seeds as payment.

And then Bodo had to buy firewood from Felix the beaver. Felix demanded 3 beans for it.

When Bodo came home with his purchases, he found that he only had 7 bean seeds left. It was very little. He thought for a long time and finally put 2 seeds in a little wooden box and said, „I’ll put those in the ground next spring!“

He cooked the last 5 beans with other vegetables. When the neighbours asked why the bean stew hardly tasted like beans, Bodo said, „Come next year for bean stew!“

This story preserves the knowledge about plant development that the children have gathered through active observation. And, of course, quite a lot of mathematics. There are also some elements of economics.

I created a picture book together with children for this story.

This became the conclusion of our bean farm and at the same time our contribution to the theme: „Harvest Festival“.

Every occasion in kindergarten enables us kindergarten teachers to introduce children to the fascinating world of mathematics.

It is about developing the understanding of numbers, quantities, operations, effects and phenomena.

We must not forget that the children have had a variety of experiences in the mathematical field long before they come to kindergarten.

It is not a new world into which we are leading the children, so we should continue to accompany them with naturalness and without fear of incompetence.

It goes without saying that kindergarten is not a place for the tedious practice of „writing numbers“. That is already the responsibility of the school. Everything else can develop into a wonderful adventure.

See also:

The Advancement of Mathematical Talent in Kindergarten

Date of publication in German: 2009, August

Copyright © Klaudia Kruszynski, see imprint.

Watching Beans Grow

by Klaudia Kruszynski

At the moment we are dealing with the theme of spring. This year we had to wait a particularly long time for it, winter just wouldn’t leave. In the middle of March, the time had finally come and we could hope for the returning life.

So we wanted to teach the children more about how plants develop. My aim was for the children to find out what factors influence the life of plants.

In a way, this project was also a continuation of the project: Time.

From observing the snowdrops growing in the outdoor area of the kindergarten, the children knew that some plants develop from a bulb that is hidden under the ground in winter. Now it was time to learn about the other kind of growth: the development of a plant from a seed.

… in a nutshell …

In this project, the children learn how to observe precisely and systematically over a longer period of time in order to come to new insights.

Little Sven (4;3) is particularly interested and can not only keep up with the older children, but is especially careful and persistent.

For this observation I chose beans and peas because they are quite large and robust compared to the other seeds. The children can see all the changes with the naked eye.

We started observing on a Monday at the end of March. It was in the afternoon, in my group there were 10 children aged 3 to 6, including Sven, Mark, Lukas,whom I wanted to involve particularly strongly in this project.

All the children sat down at the table, they were very excited about what was about to happen. I put two small bowls on the table: one with peas and the second with beans. I asked the children what it was.

I was surprised that they didn’t know raw beans, they thought they were „Tic-Tacs“. „If you don’t swallow them, then you get to taste if they are really the Tic-Tacs“.

To their horror, they realised that the „things“ were not sweets, they spat it all out.

Then I asked if they remembered what I was going to cook after work today. (I told them about this an hour earlier while painting, when the children reported what they had for lunch).

Aaron could remember: „bean soup“. Then I said that the elongated seeds are beans, and I didn’t cook those because I have something planned for them. And so most of the children saw uncooked beans for the first time. With the peas it was much easier, many children have already seen raw peas and eaten a pea stew.

All the children examined the seeds: the beans are white and smooth, the peas yellow-brown and „wrinkly“. Both types are firm and hard, you can’t bite them.

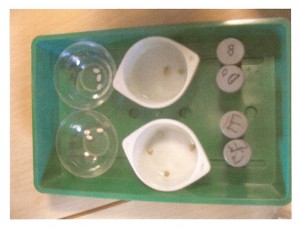

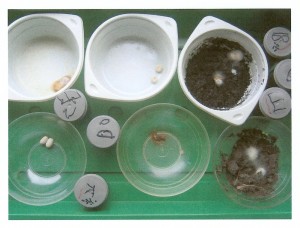

I put other small bowls and film jars on the table. Then I brought a small greenhouse from the storeroom. We still needed waterproof pens and water.

I explained to the children that we were going to do an experiment together:

„What will happen to the beans and peas over the next few days if we leave them in different environments?“

Everyone was motivated to participate, each child had something to do.

We took different bowls for the beans than for the peas, two of each kind. Sven poured a little water into one of them, the others stayed dry. Then the others put 2 or 3 seeds in each.

We did the same with the film jars and the big ones labelled the lids: B for beans and E for peas (in German: Erbsen). They also made a sign for water on one lid of each type.

I asked the children if they could imagine how the beans and peas were doing in the jars, what they „felt“?

At first the children looked at me in amazement, but because I remained serious, they got involved in the game.

Question: „What would one bean say to the other?“

Answer: „It’s wet“.

Question: „Can this bean see the other one?“

Answer: „No!“

Question: „Why?“

Answer: „Because it’s dark in the can!“

Question: „What is this bean missing?“

Answer: „Light!“

The children were very proud of their discovery.

In a moment they also knew what the peas were missing.

They also discovered that the beans and peas did not rustle in the jars that contained water. So you don’t have to take the lid off if you want to know if there is water in it.

The seeds in the small bowls have light. You can see them and don’t need a label.

Finally, we put all the containers inside the small greenhouse. We closed the ventilation flaps to keep it humid inside. We found a suitable spot on the windowsill where the box would be easy to observe.

The next day the children told the others what we had done the day before, they said that there are no Tic-Tacs in the shells, but peas and beans. No one is allowed to touch them, the greenhouse has to stay closed.

What was the best way to document

this experiment?

I decided to use photos and observation sheets because the children who took part could not yet write.

Some of the observation sheets were filled in by the children with great meticulousness. They had to observe carefully and think precisely and systematically.

I observed that Sven was particularly interested in this experiment. He is 4 years and 3 months old. He has a very good memory, quite a large vocabulary and shows a lot of activity in finding out different things. He is interested in what the „big ones“ do, chooses table games that are meant for older children. He also knows the exact rules of the game and makes sure that the children follow them.

On the other hand, he is very shy and hides his own feelings (for example, a disappointment because it is already too late for a game, or that he is sad because he lost a game). In such cases, he turns around very quickly and turns to a new activity. Surprisingly, he accepts any offer, whether it is a game or something to do or paint. When asked if he would like to do something, he seems to come out of an „idle“ or „waiting“ period. He quickly finishes the previous activity and waits for the promised offer. But he must know what it is all about – he does not get involved in surprises!

He has to understand with his head beforehand, which is not always necessary with the other children – they understand by doing. Then he is involved with his whole attention and can concentrate for a very long time – one has the impression that he would „lose himself“ in the activity and explore everything with his whole being. This is probably why he took part in the experiment.

I thought of some tasks that he could do every day in the process:

-

- Fetch the greenhouse from the windowsill for observation,

- Prepare the plate with the corresponding number for a stock photo,

- Take photographs,

- Fill in some observation sheets

or explain to the other children how to fill them in, - Return everything to the storage place.

Sven did his tasks very conscientiously. But when I asked other children to help, he wanted to run away and feigned disinterest.

The observation sheets have to be signed by the person completing them. Sven said he didn’t know how his name „goes“. The first time I guided his hand, but then I suggested that he could do it on his own. If he wanted, I could write his first name on a piece of paper for him to copy. He liked this suggestion very much, each time he took the piece of paper out of his pocket. He proudly showed it to his mother too: „This is how you write >Sven<„.

I noticed that he does not yet have a sense of direction when writing, the letters are turned on their side or upside down. This shows that he still has little interest in the technique of writing.

However, because he already showed a lot of interest in the letters, one afternoon I got him a set of foam rubber letters. Marius, who is 6 years old, picked out all the letters that form his first name from this set. Sven was overwhelmed by the set and tried in vain to find „his“ letters.

I helped him and together we put the word: SVEN on the table. Sven looked at it and asked if he could keep the letters. He couldn’t, but I could lend them to him. I put them into a small tin box and told him to bring them back when he had learned to put his name correctly or even to write it. Very proudly, he showed the tin to his mother when she came to pick him up.

Remember: Sven is aged only 4;3!

The other children, unlike Sven, only occasionally engaged with our experiment. They showed no interest in the systematic work. Only when visible changes occurred did they want to join in. But there were always „observers“ who preferred to watch what was happening from a distance while documenting.

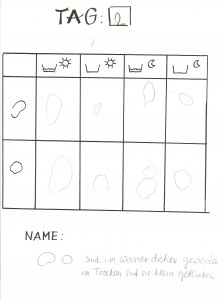

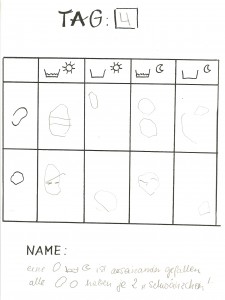

Here are a few observation sheets from the 2nd, 4th and 8th day. On these days it was little Sven’s (4;3) turn to note down the observations.

Note: The beans and peas grew thicker in the water, but remained small when dry. The observation was interrupted after two weeks due to the Easter holidays.

Note: One bean with water and without light has fallen apart, all beans and peas have two „tails“ each.

Note: Sven believes that plants grow from the „little tails“.

After the holidays we found our beans and peas dried out, mouldy or rotten. Contrary to the „prognoses“, no plants or roots developed from the „little tails“ (that’s what the children called the sprouts).

The children realised why:

Some kernels dried out because they didn’t get any water. The others had too much water.

The children didn’t know why the ones that had soil and light got mouldy. Maybe because there was no fresh air in the greenhouse, I said.

Everyone was very disappointed that we don’t get big plants.

Then I mentioned that I still have some beans and peas and we could maybe try again.

„How can we make it so we get big plants, what’s good for the seeds?“

„Soil.“ „Water.“ „Air.“

„And what else? What happened to the seeds that were in the cans?“

„They went bad and stunk!“

„Why? What was wrong with those beans and peas?“

The children gave different answers, but only Mark knew for sure: „Light!“

Then we filled a big flowerpot with soil. I opened the tin of peas and beans and the children spread them all over the surface.

I asked them if they knew how tall the plants would be. The children showed the height and width with their arms.

„Right“ – I said. „Do you think they will all have enough room in this pot?“

Wordlessly, they gathered up some beans and peas again and put them back in the tin.

Sven asked if he could fetch the water because the seeds needed it after all.

When he came back with the watering can, I asked if it was good to leave the seeds on top. Everyone said it was not good because they would be in the sun or the birds might eat them away. We decided to cover the seeds with soil. After that, Sven was finally allowed to water.

Every day the children took pictures of the pot.

The experiment is still going on. The weather is not so good yet, so it takes time for the plants to come.

But the children were curious and dug up some seeds. They noticed that the beans and peas had already become thicker, just like before, in the greenhouse. Then they carefully covered the seeds with the soil again.

A few days later, Marius brought two barley seeds that he found at his grandma’s house. He put them into the soil in our bean and pea pot. After 3 or 4 days, green sprouts had already developed, but the beans and peas had only become thicker.

I asked the children if they knew why the corn was already growing. Then Sven said that at the farmer’s the grain in the field is also green and already bigger.

„Why is the grain already so big and the beans and peas not yet?“

The answer was not easy to find, but Mark said that the grain does not take that long to grow. That’s right. And the beans and peas just take longer.

Then I told the children that some plants germinate very early, even when it’s still cold outside. It’s the same with cereals, that’s why many fields are already green.

„How does it look in the vegetable garden, are there already vegetables growing?“

„No, the beds are still black, there are only flowers in the garden“.

Then I said that many plants are waiting for the warmth. The beans and peas need a lot of warmth during the day, but they wait to grow until the nights get warmer too.

Just these days the children could see that there had been frost at night – the lawn was white in the morning.

Then we thought together about what the plants need to grow:

Water, light, air, soil and warmth.

It took a few more days before the children could observe a significant change in our pot. First, the seeds got „tails“ – I explained that they are properly called „sprouts“. Then the colour of the beans changed, they turned green. One bean split in two. I asked Sven if it would develop into a plant. At first he said yes, but when I reminded him of the experiment with the greenhouse, where the same thing had already happened, he said the bean would go bad and break.

The weather got better and the plants got bigger. The „little tails“ had become thicker and soon roots and stems grew from them. Thick leaves hung from the stems. Sven realised that they were halves of the bean. Later, the real leaves developed.

It took 25 days before we could see a significant change. The peas were still not ready, they needed even longer.

Sven made an effort to always give the plants enough water, sometimes the flower pot looked like an aquarium. That’s when I had to fall back on previous experience: „What happened to the seeds that had too much water?“

„They turned mouldy.“

„Do you think you need to water today?“

„Yes!“

„I think they have enough water.“

„No!“

„Please feel the earth, it’s damp.“

„No, it’s dry!“

And then I had an idea: „Get a Tempo handkerchief.“

But Sven didn’t understand why he should get a handkerchief, in a moment he came back without the handkerchief.

„Where’s the tissue?“

„In the bin, I’ve already blown my nose!“

One of the six-year-olds who had been watching what was happening brought a tissue.

Sven wanted to leave, but I called him back because I wanted to explain what I was going to do with the cloth.

He was to put it on the soil in the pot and press on it with a finger.

When he had done that, I asked what happened to the cloth. The other children shouted that it had got wet. Sven didn’t want to believe it, nor that the beans didn’t need water now.

The next day he did a cloth test himself, as well as in the other plant boxes that are on the terrace.

Other children also checked the soil moisture since then.

Contrary to my expectations, Lukas and Mark participated very little in this project. Lukas showed no interest in it, mostly keeping himself busy at the painting table. Mark only joined in when he had nothing to do. In discussions in the circle of chairs, he gave the right impulses – he knew what the plants needed and could report on previous changes.

Contrary to my expectations, Lukas and Mark participated very little in this project. Lukas showed no interest in it, mostly keeping himself busy at the painting table. Mark only joined in when he had nothing to do. In discussions in the circle of chairs, he gave the right impulses – he knew what the plants needed and could report on previous changes.

Mirko and Abdullah (both 6 years old) competed with Sven for the right to pick out the numbers, to water and to take photos. (Sven understood these tasks as his own).

I allowed this participation and was happy about it. All three were allowed to take turns and complement each other in the tasks.

This observation lasted several days. Every day a photo was taken to record the changes. Because nothing happened for a long time (in the biological sense), the task: „To put the next number for the photo“ took on a special meaning. We passed 10, then 20 and 30.

The children were challenged to find out the next bigger number every day. What was yesterday’s number, what is today’s, which one will come at the weekend?). At the same time, they had to put the number correctly (twenty-one as 21 and not 12).

Sven was just as good at this as his colleagues who were two years older.

My aim is for the children to discover one more factor. Plants do not only need: soil, sun, water, air and warmth for their development.

They also need time!

Different plants need different times to develop from a seed. I discovered that someone put a hazelnut in our experimental flower pot. I wonder if the children can guess how long it takes for it to grow into a hazel bush?

How long do the other plants in the garden take, how long do the trees in the forest take?

How long do people live?

How many „bean lives“ does human life take?

How many human lives does the „tree life“ last?

These are very interesting questions. I’m really curious to see what ideas they come up with. I’m especially interested in what Sven has to say about it. But also Mirko and Abdullah, who supported Sven in his „work“.

The subject of „time“ also needs time

so that the children can grasp it.

See also Klaudia Kruszynski’s article Playful Mathematics. In the section „Power“, children use the growth of beans to grasp the mathematical concept of (mathematical) power.

Observation sheet blanco (pdf)

Date of publication in German: April 2012

Copyright © Klaudia Kruszynski, see imprint.