by Hanna Vock

Beginnings of Planned Action

9-month-old David had only been going to the daycare-centre for three weeks, when the following situation occurred.

After his mother had left, little David started crawling towards the open door of the group-room, with a very happy air to him. The kindergarten-teacher saw him leaving, so she set out to follow him with a bit of distance, so David would not notice he was being followed. Later, she remarked: „I thought he wanted to follow his mum, because he crawled around the corner, in the direction of the entrance door.“ But David very determinedly crawled past the entrance door, down the entire corridor, past all other arriving parents and children, straight to the other toddlers‘ group (U3 group for children up to age 3yrs). This group’s door was also wide open, because of the arriving children’s bustle. David crawled straight to the ball-pit, throwing himself into it with a yelp of joy.

The ability to make plans, drawings and mind-maps are understood as tools of mental activity in this context. Gifted children are often very eager to acquire these tools at a very early (pre-school) age.

The background to this extraordinary story:

David, who had stuck out for his extremely good memory, excellent spacial sense of orientation and indications for a special logical-mathematical talent later on, and time and again, had spent the first three weeks of daycare-time mostly in the ball-pit in his group. Because the house only had one ball-pool, it was shared by moving it from group to group after a while.

A day before the „crawling incident“, David had visited the other group’s room for the first time, re-discovering the ball-pool and playing in it.

The following morning, he had realized the opportunity (an open door) for making and putting a plan into action.

How good of the Kindergarten-teacher not to prevent his trip and bring him back to his group. Instead, she let him carry out his plan, and followed him, because she wanted to see where he was headed.

What exactly had all occurred in this baby’s mind?

-

- He had developed a strong liking for the ball-pit.

- He missed it when it was gone.

- He re-discovered it and mentally placed it to be in the other group-room.

- He remembered this discovery and the place the following day.

- He saw, interpreted and pursued the open door as an opportunity.

- He knew the way to the other group-room!

- He was curious and brave enough, using his resources (the ability to crawl) in order to make and find his way independently.

- His expedition lead to the desired destination and a heart-felt success.

- He was allowed and could thus experience a sense of freedom and a great amount of self-efficacy.

Sometimes you need to (literally) follow a child, in order to understand what is going on in its mind.

All of the above listed points are important for a successful learning process.

Also see: How does learning happen?

David’s plan was an action plan: „I want to crawl to the ball pool.“ This plan splits up into the following subordinate plans:

-

- Leave my group through the door,

- crawl down the corridor,

- turn at the corner,

- crawl down the long corridor, past the entrance-door

into the room where the ball-pit was, - locate the ball-pit in that room,

- jump in and have fun.

Also see the paragraph on „Algorithms“ in the chapter on Basic Ideas of Mathematics.

Linguistically, he was obviously not yet able to verbalize his plan. Each single step (for example: turn at the corner) may have actually materialized during the expedition, yet, the initial as well as the desired final destination of his plan, must have already been in his mind from the beginning.

Let me tell you about what I’m planning to do

With increasing age, and at some point within their development, children are able to verbalize their plans (if and when someone empathetically shows interest and follows track), and after that, they are able to write down or draw the plans they have in their minds.

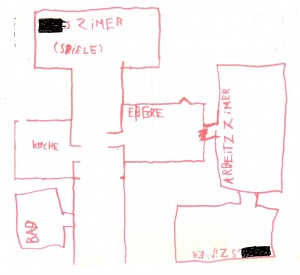

The IHVO-graduate Birgit Wester experienced an amazing method of orientation of a 2;10 year-old boy in her group. She writes as follows: „During his first days at kindergarten in the Rainbow-group he wants to visit the Sunshine-group. This is the layout of our floorplan:

He says to me: „I’m going to the group, where I have to go round the corner.“ I have never heard such a statement from a 3-year-old. It proves that he has an exact picture of our rooms and layout in his mind, shortly after having only started going to kindergarten.

More precisely, this means that he can verbalize the plan which exists in his mind. Unfortunately, we do not know in this case, from which point onwards exactly he could develop such a (pre-verbalized) mental plan.

The following example shows the outline sketch of an apartment’s layout, which a girl aged 5;11 drew. The order of the rooms, their orientation and direction is correctly reflected, even though she forgot her parents‘ room and of course all of the rooms lay immediately next to each other.

This demonstrates the ability of a spatial orientation on another level:

In each case, there was a good mental plan – in David’s case, the 9-month-old, it could „only“ be put into action actively; the almost 3 year-old could verbalize his plan; the 5-year-old was able to draw a sketch and label it.

The word PLAN has 3 different meanings in the German language: Firstly, it stands for a spacial classification (for example the map of a city or the layout of a kindergarten). Secondly, it stands for schedules (such as a train schedule) and thirdly, one can also use the word to talk about planned action and events in the future.

Both of the aforementioned examples depict a combination of both, the layout and the plan of action. The second example includes spoken language as a means of the child’s expression.

See also: Our Village in the Woods.

The following example introduces a child which has begun to write, noting down it’s self-created mental plan of action:

The daily schedule of a 6-year-old:

→ Plan: Clean room + clean surfaces. Go shopping. Go see Lena. Return wagon. Return items. Play.

One can clearly sense a need for planning and structure to a certain degree. Putting the plan into the form of a written list was most probably inspired by (parental) role models.

Making layouts

Plans are abstract reductions of the real world. A line can represent a street, a green spot may stand for a park. The purpose of a good city map is obviously to be well-arranged and clear, offering just enough information for a stranger to find his or her way in the real city.

Any unnecessary details (for example whether a house has two or four floors; whether there are flower boxes in the windows, or whether a house was built in 1920 or 1975 or whether there are 5 or 10 shops in this street) are omitted. Any essential information (where a street curves, where train tracks cross the street, where there are buildings or trees at a street) has to be represented.

It can be very appealing to draw the outline of the layout of a kindergarten with children, including all the essential information – and thus realizing, that you first have to agree on what exactly is important to whom: Children may find a playground important, a motorist will be interested in a petrol station, senior citizens may want to know the location of a pharmacy or a grocer, and all pedestrians care about pedestrian crossings.

Such a project requires walking around the respective area, correcting the plan or map over and over again, according to the children’s observations.

Will everything fit on paper? What kind of scale should be used – and what exactly is a scale? These are all questions one can face during the progress of this kind of project.

Sketches and drawings, learning to draw

Being able to make a quick sketch or drawing can be a helpful support for the documentation of memories and may also facilitate communication with others. Many people are convinced they cannot draw. But here one should note: This tool of mental achievement can very well be acquired at a very early stage. One can practice detailed observation, as well as putting it on paper. Of course, talented drawers will clearly have an advantage. All aspiring artists go through a lot of drawing and sketching at the beginning of their studies. At kindergarten it is advisable to distinguish between artistic drawing and painting on the one hand, and the precise detailed drawing of real objects on the other, alternating between the two or combining them as well.

See: Drawing Course with Linda.

I highly recommend the titles listed below when practising how to draw in kindergarten. After an initial introduction by the kindergarten-teacher, children will be able to continue independently and experience their own achievement and success.

→ „Children learn to draw and paint“, by Alex Bernfels and Rosanna Pradella, publisher: christophorus

→ „For young illustrators and designers“, by Iris Prey, publisher: Bassermann

→ „Drawing vehicles – step by step“, by Norbert Pautner, publisher: Tessloff

→ „Drawing animals – step by step“, by Norbert Pautner, publisher: Tessloff.

See also: Drawing Exercises at 4

Mind-mapping

Mind-maps are not only for grown-ups. Important people and teams made up of distinguished people create mind-maps. Children are also important people.

Mind-maps were once invented by the British psychologist Tony Buzan, in 1971. This tool for mental labour or achievements soon found enthusiastic supporters and practitioners around the globe and the English term mind-map is literally translated as a mental or memory map.

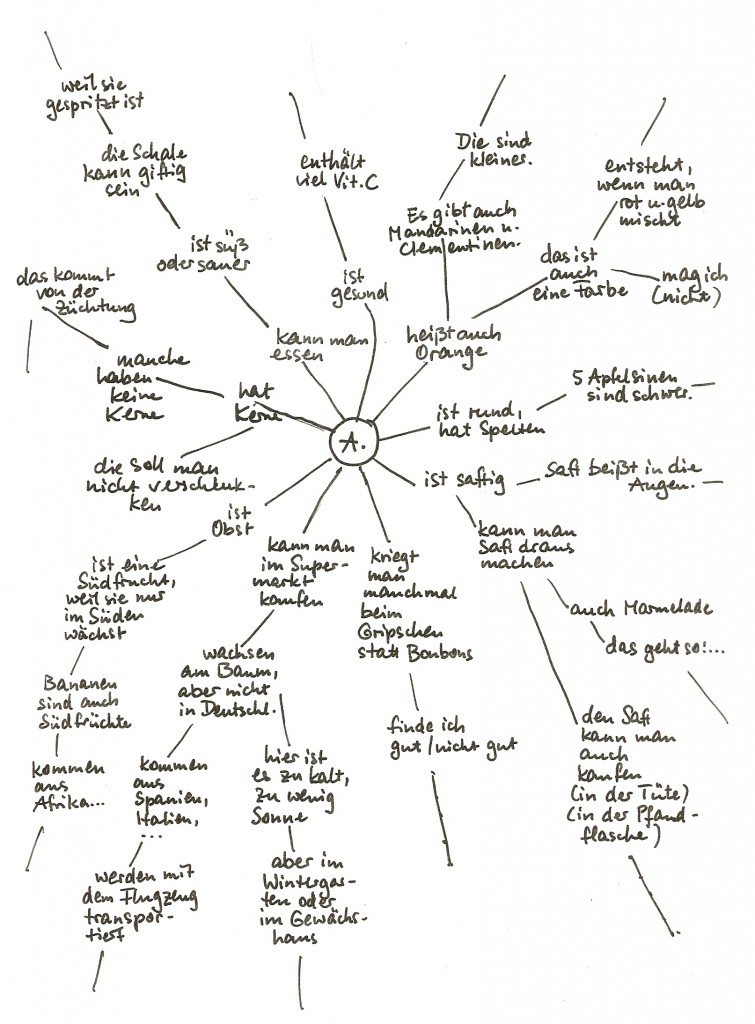

The mind-map displayed below, features the letter A located in the centre. A stands for the German word for Orange (Apfelsine). This letter A, in the centre of an empty sheet of paper, was the beginning of a collection of associations for the concept of the term orange, from a group of kindergarten children. Each newly found concept, such as the origin or edibility, was added to the mind-map with a new branch.

See this mind-map in English.

Certainly comparable mind-maps could be created for other terms.

Mind-maps can be set at the beginning, as well as at the end of a project:

At the beginning, in order to collect ideas or at the end, in order to visualize and document the content and phases of an undertaken project and the information and insights obtained during it.

See also: Advancement through Projects

As soon as gifted children have learned to work with and apply mind-maps as a tool, they will find their own applications.

Copyright © Hanna Vock, see Imprint.

Date of publication in German: May, 2011

Translation: Sonia Wagner