by Barbara Teeke

In scientific literature one may find different positions and considerations on differing approaches to an understanding of what we mean by giftedness, while it is generally agreed upon that a comprehensive and final definition of giftedness is yet to be established.

(see Stapf 2003, Fleiß 2003, Heller 2001).

In short:

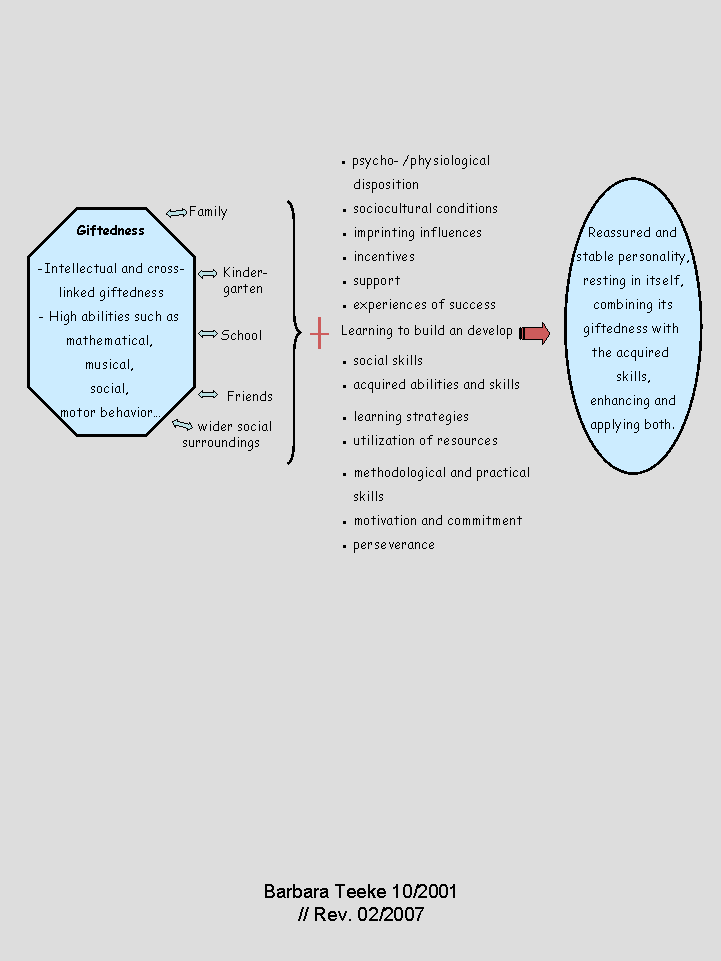

This concept distinguishes between two types of giftedness:

One being the intellectual and cross-linked / integrated giftedness and the other being high abilities in particular domains.

Giftedness will here be seen quite literally as a gift, something a person is given, or more scientifically a disposition.

This gift is interdependent with the most differing influences accompanying the child, imprinting it and – in case of a positive course of events – help the child attain a self-concept which enables it to encounter the world in an affirmative and stable mindset.

This concept integrates quite intentionally the influence of the kindergarten since the pedagogic personnel working there has – aside from the family – an important attentive and supportive part in the development of the child.

Another difference of this model as compared to others is that (quantifiably) outstanding achievement is not considered to necessarily result from giftedness. Yet that for a person, who has received adequate support and who stands firmly in life, achievement will naturally follow as a result of an inner urge, that in such case achievement is an inherent characteristic of that person.

Several concepts such as for example the Münchner Hochbegabungsmodell [Munich Concept of Giftedness] by Heller, Perleth and Hany or the Mehrdimensionales Begabungskonzept [Multidimensional Concept of Giftedness] as proposed by Urban disclose the interaction between nature and nurture and its actual representations. Further conceptions are vividly depicted in Holling/Kanning (1999) and I recommend them for reference.

Personally I agree with Holling/Kanning in that the diagnosis of giftedness is strongly dependent on the underlying definition (see: Holling/Kanning).

For well-grounded diagnostics a corresponding idea of man is mandatory. I will therefore at this point outline my position on the issue of giftedness.

I am convinced that giftedness or any high ability comes to an individual as a gift – granted at birth. This gift is cathected positively and calls for being accepted and nurtured.

Prerequisites for the Evolvement of Giftedness

Two types of giftedness may be distinguished:

Type 1:

Intellectual and Cross-Linked / Integrated Giftedness

In this the higher intellectual faculties are taken as a starting point for the development of complex, sophisticated and excellent thinking.

This fundament cross-links with further faculties from different domains, which are not coequal and are not to be mistaken for points on a checklist:

- intellectual creativity

- curios-mindedness and a thirst for knowledge

- enthusiasm and devotion for specific areas of interest

- cross-linking with abilities from such domains as (for example) mathematics, music, language …

Type 2:

High abilities in particular domains as for example

- mathematical,

- musical,

- social,

- excellent motor behaviour.

For illustration: For a person with outstanding accomplishment in the area of sports this particular giftedness may not extend to other domains let alone intellectually cross-linked thinking.

If intellectual giftedness were to be considered separately it would be no more than just that: a high ability in a particular domain.

However, my experience has been that gifted people dispose of a wider range of highly interconnected abilities than do people of high abilities in particular domains.

The gift of giftedness underlies the interaction of different influences:

Foremost is the psychological and physical disposition of the individual child.

Next to be considered is the immediate circle of persons affecting the child from the moment of its birth: its family. It is the other members of the family who provide for the child’s earliest impressions and experiences.

Next come kindergarten, school, friends and the wider social surroundings. Each one of these affect the development of the child and its self-concept. It is up to them which experiences the child will make, which challenges it will face and master, which and how much support it will receive.

Additional influences are the socio-cultural conditions under which the child grows up, imprinting influences, incentives, support and mediated experiences of success.

As the socio-cultural conditions under which a child grows up can hardly be altered it is also important for the entire group of the gifted that they meet people from different walks of life who recognize the children’s high abilities and skills and accompany them providing support and stimulation. A systematic support of the gifted, too, is necessary to help them develop a positive self-concept. This requires challenges which are geared not to their age but their individual needs, abilities and skills enabling them to grow further and beyond. This trying for and going beyond limitations should be accompanied by the experience of success. Success being the joy and satisfaction of having achieved something as well as the joy of this being acknowledged by others. As much as this may appear to be an everyday reality, for the gifted it isn’t necessarily so. They rarely find themselves in a position where they get to grow beyond themselves and learn something new – and all that at a point when it suits their individual pace as opposed to the pace set by their peers in age.

These requirements and influences being complemented by the adoption and development of

- already existent abilities and skills

- learning strategies

- utilization of resources

- methodological and practical skills

- motivation and commitment

- perseverance

Especially social skills are often seen to be a critical point with the gifted child. It isn’t uncommon that a gifted child’s social skills are seen to be in blatant contrast to its other skills. So it is that oftentimes parents of gifted children are told by kindergarten teachers that their child is with regard to its cognitive ability absolutely ready for school, yet its underdeveloped social skills make enrollment at school appear premature.

This may be true for a certain percentage of gifted children for whom customary enrollment at school would be reasonable in order for them to develop further skills, enhance them and make positive experiences which up to that point have not been made (for example the experience of having a friend).

For all other gifted children social skills are not an issue of concern as long as

- they are integrated in a group of similar competence

- they enroll at school and are finally allowed to learn and study

- their early enrollment enables them to meet with older children disposing of skills which the gifted child has not found among the younger children of its kindergarten peer-group

Acquiring learning strategies, learning how to learn, is also very important for gifted children. They learn many things as if “picking things up while walking along” without much effort and therefore are oftentimes way ahead of their classmates. At the same time it is often hard to accept for gifted children to concern themselves with issues and topics which are of little interest to them.

In the end such tending to the individual needs of a gifted child will result in the child’s reassured and stable personality, which rests in itself, talents and skills being combined, applied and enhanced continuously.

Some annotations to complement this concept:

- It is quite intentional that the important role of kindergarten is being introduced into these reflections since it is rarely appreciated in such considerations. This is how other concepts may easily seem to suggest that giftedness does not occur any earlier than at school, which is wrong. By the same token gifted children oftentimes first attract attention at school when overachieving or failing to meet requirements. Yet, precisely this may be necessary to eventually recognize and foster to the individual needs of the child, ensuring an adequate support and a substantial improvement of the child’s overall situation. However, in an increasing number of cases kindergarten teachers recognize gifted children among their groups, especially after having profited from further trainings on giftedness.

- When considering different concepts of giftedness one may find at the heart of many of them a rationale targeting the expectation of higher performance as a result of giftedness. These concepts assume that a gifted person will show outstanding performance and can be defined by such.

This approach, however, neglects the phenomenon of the so-called underachiever (person with a high IQ yet minor achievement). An insufficient approach therefore, resulting in the perpetuation of a fatal disregard for the child’s actual needs throughout the years of kindergarten and school.

We deliberately choose to focus on the human being in its humanity rather than in its potential performance. I am convinced of this: If a human being experiences recognition, acceptance and integration, if that person is confronted with suitable challenges and receives adequate support, then high performance will result as a natural consequence, fueled by an inner urge and representing an inherent character trait of the gifted personality.

Date of publication in German: May 5th, 2007

Translated by Arno Zucknick

Copyright © Barbara Teeke, see Imprint

Do the authors of this make any mention of the Iowa Acceleration Scale: A Guide for Whole-Grade Acceleration Grades K-8, developed by professors Susan Assouline and Nick Colangelo? This scale, which is based on more than ten years of nationwide research, is successfully used by schools in every state in the U.S., as well as in Canada, Australia, and other countires., and it is based on research that identifies the factors related to successful early entrance or whole-grade skip. As far as I can tell, it is the only systematic, reearch-based way to decide whether or not to accelerate a child by a whole grade, and I would recommend that the authors consider integrating that information, if it is not already there.

James T. Webb, Ph.D.