by Antonia Herberg

I want to help Manuel (5;3) to develop a different role in his group of children. Very often he is in the role of the clown and the troublemaker.

My way will be to offer him situations in which he comes across to the other children with his interests and abilities and lets his positive potential come to fruition. I also hope to strengthen him by creating friendships.

Manuel should be given opportunities to pursue his urge to explore and learn. At the same time, I want to show him ways to let his things benefit the group of children, to get involved, to let himself and the other children experience that he is an enrichment.

This includes the offer that he presents his results in the chair circle. There should also be an attempt to involve other children in his activities.

A first observation and assessment of Manuel can be found here: Manuel, 5;0 years.

1.

In the last few days Manuel (5;3) has repeatedly taken the (Montessori) offer >lighting a candle< during free play. His attention was clearly focused on the moment when he put out the candle with the wick extinguisher. He did this very slowly each time and let the candle flare up again and again.

To give him a new opportunity to observe the extinguishing of the candle, I provided a candle, matches and a glass for him.

When he gets the candle again the next morning, I ask him if I may show him something else with the candle. Manuel looks at me attentively and agrees. I demonstrate the procedure to him once, Manuel laughs and repeats it several times. He puts his head on the table top and watches the candle go out.

I ask him if he knows why the candle goes out under the glass. He replies: „There’s no air left.“ I offer him a bigger glass. He takes it and says, „It gives her more air.“ Manuel tries it out. When I offer him a second candle, he lights both of them and puts the glasses over them at the same time with both hands and watches curiously what happens.

He asks if I have a very small glass. He extends his observation to five glasses of different sizes, sets them up in an line and one after the other he puts the glasses over the candles with rapid and coordinated movements.

After several passes he beams at me and says: „This is such fun, I’m going to use up all the matches.“

At the end of the free play I ask Manuel to show the other children in the chair circle what he has done and explain it to them. He thinks, smiles and nods.

Everyone sits in a circle, Manuel sits next to me and in front of him stands the tray with the candles, glasses and matches. The children are waiting. I ask Manuel quietly if he can tell them now what he is going to do. Manuel shakes his head, leans over to me and whispers: „You!“

I say a few sentences to the children and Manuel starts lighting the candles. Before he puts the glasses on, he looks seriously and says: „This has to be done in a hurry.“ His performance succeeds. He explains that fire needs air to burn, that there is different amounts of air in the glasses and that the candles go out one after the other. The children are attentive, listen and watch.

I thank Manuel and hand over the chair circle to a pre-school child. Then I leave the room and the children play under the guidance of the big boy for about 45 minutes. When I return, I see Manuel playing in the circle with a satisfied and happy face.

Remark of the course leader:

He begins to share his insights. And he experiences success: first in his investigations, which lead him to new insights, and then the social success that the children follow him attentively during his presentation. This brings good feelings.

2.

Manuel repeats the game with candles and glasses. He acts independently and very concentrated and makes several passes. His attention is obviously focused on putting the glasses over the candles at a fast pace in order to achieve synchrony at the start. (He has set this task for himself.) Sometimes a candle goes out. Then Manuel says „Shit!“ and starts again from the beginning.

Opposite Manuel sits Ole, who is the same age, working with the electric box. After some time Manuel observes Ole, who does not succeed in his task. Manuel gets up, walks around the table, takes the screwdriver out of Ole’s hand and builds an electric circuit. Then he sits back down on his chair, looks at Ole and says smiling: „That’s how it works.“ They talk about their work. Manuel gets up again after a few minutes, stands next to Ole, then fetches his chair, sits down and watches Ole in silence for a quarter of an hour. Then they both tidy up and have breakfast together. They happily talk about what they like to eat.

Note from the course leader:

Two researchers and inventors have found each other!

3.

Manuel gets the offer to grind different raw materials with a mortar. He is concentrated and works on it for over two hours. He keeps looking closely at what is happening, what is changing in the mortar. In the circle of chairs he presents his work confidently and safely.

Note from the course leader:

Oh! What progress after just one positive result. He has learned how to present. Here, too, ease of learning is evident.

4.

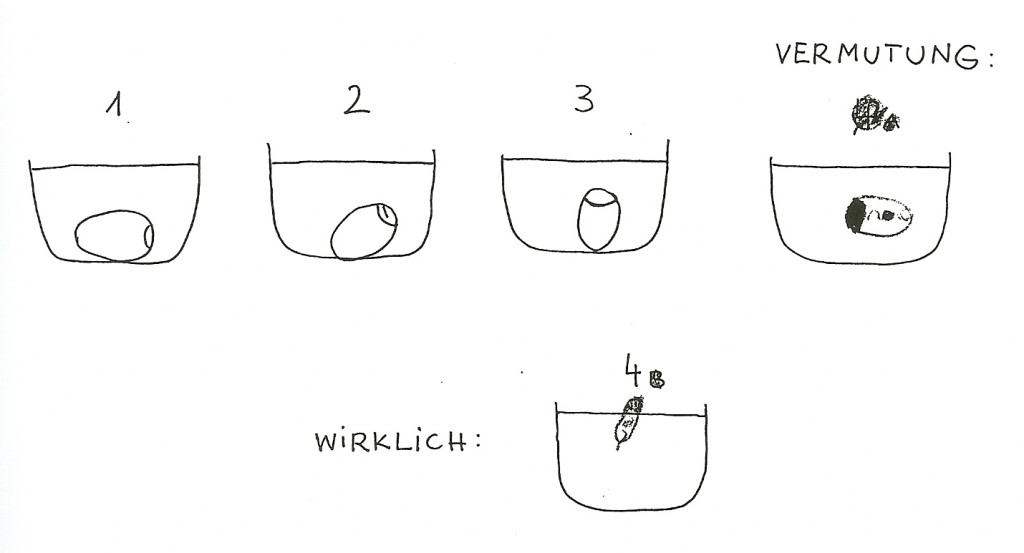

On the table are white daisies in a vase. I ask Manuel, „Do you think daisies drink the water?“ He nods and says, „Yes, all plants need water.“ I go on asking if you can see that they’re drinking it. Manuel ponders for a moment and says, „Yes, with a magnifying glass.“ I give him a magnifier and he looks intently at the stems through the magnifying glass. After a while, I ask him if he has observed anything. He shakes his head and says, „I don’t see anything.“

I point out to him that the water in the vase is transparent, that it has no colour, and suggest that he colour it, then the flowers would have to drink coloured water. He looks at me and asks, „What happens then?“ I ask back, „What do you think might happen?“ He touches a blossom and says, „Will it turn colour?“ I ask him to try it and give him a stand with test tubes and red and black ink.

Manuel carefully fills the ink and puts two daisies in red and black ink. Then he sits in front of them, crosses his arms and looks at the flowers. After ten (!) minutes he comes to me and says with a plaintive tone: „Nothing’s happening.“

We put the stand with the flowers on the windowsill and I invite him to do something else now and to have a look in between.

At the beginning of the circle of chairs I ask Manuel to explain to the children what he did with the flowers. He laughs and says, „Yes, I want to do that.“ Manuel tells the children with a lot of facial expressions and a loud voice about his experiment and that he is now waiting to see if anything has happened. The children listen even more attentively than at his first demonstration. Manuel speaks freely and doesn’t even pay attention to me anymore.

When about half the time in the circle of chairs is already over he jumps up and shouts: „There, it starts! One flower is already turning pink.“ Manuel is beaming and all the children look at the pink flower. When he leaves, he says, „Black takes longer.“

5.

Manuel is still interested in the mortar. Every day, something different is pounded. He presents the results again in the chair circle and finds companions who share this passion with him.

Note from the course leader:

This is where the attention you give Manuel begins to have a distinctly positive effect on the group.

6.

Manuel is back from vacation. He heads for the sandpaper letters and says: „Antonia, do you know I can read a bit now?“

I reply: „No, but you could show me.“ He grins and names all but two of the letters. Then he says, „I want to rub them all in and make a book with them.“ He spends a long time doing it, concentrating.

7.

Manuel is always busy with the letters. He talks about secret writing and I show him mirror writing using my name. He is enthusiastic and tries a lot. Among other things, he glues a printing plate and is happy about the mirror writing when printing. In a circle of chairs he explains the mirror writing to the children.

8.

Today Manuel makes an envelope out of paper, writes something on a small piece of paper and puts it into the envelope. I ask if I may see it. He hesitates and then says resolutely: „No, you can’t. It’s a secret!“ I laugh and say, „What a pity.“ Manuel says, consolingly: „No matter. You couldn’t read it anyway because it’s a secret writing.“ Then he puts it in his drawer and says, „You can’t show it secretly in a circle of chairs either“ and laughs again.

Note from the course leader:

Now he is free to choose what he wants to show you and the other children. Again a learning progress.

9.

Manuel now works more often together with other children, today with Ole. They invent patterns with geometric shapes in graded sizes, rework the shapes with coloured paper and stick their „invention“ on.

10.

Today morning, Manuel comes in and says: „I know what I want to do. I’ve always wanted to work with a web frame.“ We prepare a frame for him. He gets the hang of it quickly, weaves persistently and doesn’t let himself be put off even if he makes a mistake. He then gets help and continues. He carefully chooses the colors by holding them to the piece he’s already woven.

11.

Manuel and Hans have worked together more often in the last few days. Today, in the morning, they walk towards each other determinedly and make an appointment for the building room. Emil asks if he can join in too. Hans and Manuel build a rail network with the Brio Bahn. Emil plays beside it alone with a locomotive and trailers. Manuel and Hans talk to each other and present their plans and actions. Manuel says: „Hey, when are we going to connect the rails, by thunder?“ Hans and Emil laugh and fling the rails across the room. Manuel: „Hey, why do you destroy everything? It doesn’t work that way. I need a long run. When are we going to tie?“

The other two kids keep messing around and laughing. Manuel gets upset and swears and shouts: „Stop! It’s not going to work!“ When the both don’t react, he starts throwing things around.

Note from the course leader:

The desperation of the highly motivated when others torpedo the construction work.

I intervene and ask Hans and Emil to listen to Manuel. They do, and Manuel describes his plan. They are rebuilding. I invite them to put trailers on all the locomotives. Manuel tries, distributes, rearranges again and says: „Oh shit, I wanted one with four trailers. But I can’t do that. Then two engines won’t have any.“

He fiddles around for a while. „I’ve got it! We’ll each get one first.“ He does it like this, looks and comments: „That’s justice.“ They start playing. Manuel comments on his moving train: „Move the longest distance. Oh, station forgotten! Station! Stop the train! Next please! Next, please!“

Note from the course leader:

I’m glad you helped him. He learns: I have an idea, a plan in my head. If I want others to go along with it, I have to introduce and explain it to them.

12.

Manuel comes in the morning and says: „I have to check my leaf. I’m very curious.“ A few days ago he brought a big leaf from his trip to the kindergarten and put it in the flower press.

The leaf is not dry yet. He looks at it and feels it and says, „Do you think it’s ready?“ When I say no, he says: „Then it must go back in“ and clamps it again.

Note from the course leader:

He shows real talent for research, such as constant interest and perseverance in his projects.

13.

Manuel arrives at the kindergarten in a good mood. He goes to his workplace from the day before to print his name with the printing plate he has made. He chooses the colours, mixes a shade of colour and applies the ink evenly with the roller. He prints for the first time, looks at the result, laughs and shouts happily: „Everything’s back to front!“ (Mirror writing.)

He makes several prints, then tidies up his workplace and strolls through the group.

14.

Manuel sits down at the table where the children do folding work and begins to fold. I ask him what he is folding. Manuel: „I just fold. Let’s see what comes out of it.“

Very concentrated he tries it out. The result is a regular folding work, where all folds correspond to each other on the right and left. Hans comes and watches him. Then they both fold „just go ahead“ and show each other their results.

Manuel holds up his and says: „It looks like a plane. I must try it out.“ He likes the test flight and he repeats the folding in a different colour. Then he tidies up and goes for breakfast.

Then he purposefully fetches his weaving frame, holds a ball of wool to the woven piece, mumbles something, puts the wool away and takes red wool. Again he holds it to the woven piece, says „yes, good“ and begins to weave. His movements are relaxed and concentrated. He does not look at what is happening around him.

15.

Again and again Manuel asks to mortar. It almost seems like a ritual of arrival in the morning. Another child always joins in and they enjoy this action together.

16.

Manuel watches as I show a boy of the same age something with brown stairs and red poles (Montessori material). He gives advice on the construction. With the agreement of Konrad he plays along and they try out all kinds of things with a lot of fun. The common play continues throughout the whole morning.

When Manuel arrives and I greet him, I ask: „How does it look like? What do you mortar today?“ Manuel replies: „No, today is the day when I stop using mortars. Today I’m going to the site with Konrad.“ They disappear into the construction corner, and there they’re in good spirits all morning, building a huge railroad.

18.

Manuel plays the role of the wolf in „The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids“. He plays with commitment and the right stakes. When the little goats finally dance, singing, around the fountain into which wolf Manuel has fallen, he jumps up and runs to his seat.

We talk in a circle of chairs about how we enjoyed it. I ask Manuel what suddenly happened to the wolf in the well. Manuel says: „I thought this thing was stupid. I don’t want to be dead.“

19.

Manuel plays with four-year-old Mira. He builds a rhombus with the (Montessori) poles and shows it to the kindergarten teacher. She makes a new suggestion. Manuel says, „No, I want something else.“ He explains with hands and words what form the building should take. The teacher asks, „Like a funnel?“ He beams: „Exactly like a funnel!“

His plan succeeds and he dances enthusiastically with Mira around his work.

Reflection

Manuel has received our support to experiment a lot and to try out new things in the kindergarten as well as to deepen and expand material work.

Our support consisted in

-

- to prepare offers for him which we assumed would interest him,

- to get involved with his guidelines and ideas and to be available to him when he implements them.

Several times he presented his work in a circle of chairs. The group reacted with curiosity and recognition. There were imitators of his work, whom he helped with words and deeds, and also other children presented their things in the circle of chairs.

In the meantime this form of presentation has become part of everyday life and enriches the group life.

Increasingly, play situations developed in which Manuel acted well with children of the same age and also much younger children. His basic mood, which he showed in the kindergarten, changed at an amazingly fast pace. He now comes to the kindergarten full of energy and happy.

He hardly ever takes on the clown role anymore, but acts very humorously, with a lot of wit and joy in situation comedy.

He actively participates in the chair circle offers. As a play partner, he is now in great demand among the children.

Since a few weeks Manuel is also at the kindergarten over lunchtime and can play intensively with other children in the afternoon in the smaller group. We had suggested to the mother to try this step, because it had become clear in conversations with the parents that Manuel (he also has three siblings) was straining the family and himself with many fights at home.

He accepted the afternoon care with enthusiasm. I don’t take this for granted because his younger brother is always picked up before him and has lunch at home.

During this time of targeted demands and attention, Manuel has been able to stabilise his emotional state and his social position in the group through offers and has gained in self-confidence.

Conflicts are handled by him in a relaxed and appropriate manner.

He has a clearly friendly relationship with the teachers, which sometimes has an almost complicit character.

Note from the course leader:

Well, it’s the best thing that can happen to gifted children.

Further considerations

In the last two weeks I have increasingly withdrawn, a colleague (who already has the IHVO certificate – see also: Journalism in Kindergarten) has taken over his company in a very competent way over the weeks. I took this step because of the necessity of everyday life (devotion to other children) and also because I felt that now was the right time to let Manuel go his own way more often. In this way I want to avoid that he only experiences himself as good when he acts close to the adult. It is important to me not to let my attention for him diminish – but to find the right balance in the attention so that Manuel continues to experience and behave as a member of this group of children and his independence grows.

I am confident that we will succeed in this as a team of kindergarten teachers and that Manuel will be able to take further positive steps in his development with his new starting capital of competence.

What impressed me very much about this project was the extent of the profit for the other children. Some children, imitating at first, but then according to their own needs, demanded new forms of play for themselves and also made use of them again for the group.

During this time, we adults were able to discover many new things for our work with the children in general and also specifically with Manuel. The next step for me will be to see exactly when Manuel needs new input and where he can go on alone. Manuel is so enthusiastic about every suggestion that as an adult you might be in danger of slipping into the role of an animator. I would like to observe and reflect on this with myself.

Remark of the course leader:

I don’t see the danger that you could become an animator (i.e. just entertaining and „joking“ him. Manuel implements every suggestion very independently and also has his own ideas… The more of them he can successfully implement (with support, also by further questions; where it makes sense), the more good ideas he will produce himself.

Very often Manuel comes to the kindergarten in the morning and has his own plan in his head and knows what he would like to do. I want to provide him with the necessary means to do so and thus support him in following his own development plan, his own learning paths in and with the group.

(All children’s names have been changed.)

Date of publication in German: April 2020

Copyright © Antonia Herberg, see Impressum.